- Home

- Elizabeth Letts

Finding Dorothy Page 2

Finding Dorothy Read online

Page 2

“Perhaps a young man like you wouldn’t remember…” Maud was unable to hide the discouragement in her voice.

“No, ma’am. This is all news to me. But I promise you, it doesn’t matter one bit. I may not recall anything about the author, but I’ll definitely never forget that story!”

It pained Maud terribly to think that Frank could be forgotten, and yet, she wasn’t entirely surprised. Now, almost twenty years after her husband’s death, many people didn’t recognize his name, but was there anyone, big or small, who didn’t know Dorothy and the Scarecrow, the Tin Man and the Lion? Frank’s creations had grown more celebrated than their creator, bursting out of the confines of the pages to which Frank had entrusted them. Of all people, Maud knew best that none of it—the Wizard, the Witches, the Land of Oz itself—would have existed were it not for the real flesh-and-blood man who had walked this earth, who had lived and laughed, and sometimes suffered…

“Mrs. Baum?” LeRoy was holding the book out to her. Maud realized she had been lost in her thoughts.

“Well, it’s been a pleasure.” He turned to go.

“Mr. LeRoy?” Maud held out her hand.

“Yes?”

“Do you think that you could…Well, it’s just that…You see…I’m the last link to the author of this book, and yet I can’t even get permission—”

“Mister LeRoy,” Ida Koverman interrupted.

He pivoted to Mrs. Koverman as if surprised by her presence. “Well there, Ida,” he said jovially. “Do you know who we have here?” He held up the book. “This is Mrs. L. Frank Baum! Can you believe it?”

Mrs. Koverman’s eyebrows remained fixed in a straight line, matching exactly the cast of her mouth. “Mr. Mayer will see you and Langley now.”

At the mention of Mayer’s name, the two men were suddenly all business. Langley muttered, “Good day,” LeRoy tipped his hat, and Maud realized that their brief conversation was over. The two men hurried inside the confines of Louis B. Mayer’s office without a backward glance, leaving Maud no choice but to return to her seat. Half an hour later, when Mayer’s door pushed open and the two men emerged, Maud stood up expectantly, hoping to engage them once again, but this time, deep in conversation, the men barely nodded to her as they passed, and she soon found herself alone with Mrs. Koverman, who was typing with a rapid-fire clickety-clack, clickety-clack, zing.

After what seemed an eternity, Ida Koverman stood up and beckoned. The door swung open upon an office so vast that Maud could have ridden a bicycle across it. At one end stood a pearly grand piano; at the other was a massive white semicircular desk. Behind the desk sat a round-faced, bald-pated man with equally round spectacles. To Maud, he looked like a prairie dog just emerging from his hole. He seemed to take no note of her at all but was rummaging around on his desk, leafing through some papers that might have been a script. Behind her, Mrs. Koverman exited, leaving the door open. Maud stood still, waiting for some sign of acknowledgment; at last, certain that none was forthcoming, she approached.

Louis B. Mayer looked up, as if startled to see her there. “Mrs. L. Frank Baum,” he burst out, jumping up from his seat. “Mrs. Oz herself.” He stood up and reached across the desk, pumping Maud’s hand warmly, then dropped it suddenly, taking a step back as if seeing her for the first time. “So tell me, Mrs. L. Frank Baum. What can I do for you today?”

“I’m here to offer my services,” Maud said. “I called the moment I saw the announcement in Variety.” Maud did not mention that the studio had been rebuffing her overtures for months. “I want to be a resource to you. I can tell you all about Oz, and about the man who created him. Nobody knows more about the story than I do—”

Mayer cut her off, calling through the open door.

“Ida?”

Mrs. Koverman popped her head in.

“Mr. Mayer?”

“Bring that box of letters in here, will you?”

A moment later, the secretary deposited a large box on the desk.

“Be a doll and read us a couple.”

She sifted through the box for a minute and pulled out an envelope, from which she extracted a letter.

“Go on,” Mayer said.

Mrs. Koverman began to read in a high-pitched singsong: “ ‘Dear Mr. Mayer, please make sure that you don’t change anything in the book. Sincerely, Mrs. E. J. Egdemane, Sioux Falls, South Dakota.’ ”

Maud sat up straighter in her chair. “Ah yes, the mail. We used to receive it by the wheelbarrowful. The fans are so passionate. Did you know that my husband used to incorporate suggestions from children into the storyline whenever he could?”

Mayer sat impassively, hands folded on the desk in front of him. Maud couldn’t decipher his expression.

Mrs. Koverman rummaged around and plucked out another, as if picking numbers for a game of Bingo. “This one’s from, let’s see…Edmonton, Washington. ‘Dear Mr. Mayer, Nobody can play the scarecrow like Mr. Fred Stone from the Broadway show. Please see to it that he is cast in the movie.’ ”

Mayer grinned. “No matter that old Fred Stone has hardly been able to walk since he got wrecked in that airplane stunt, never mind dance.”

“Stone is quite recuperated,” Maud said tartly, but Mayer was still nodding for Mrs. Koverman to continue with her recitation.

“ ‘Dear Mr. Mayer, My name is Gertrude P. Yelvington. I’ve been reading the Oz books since I was a young girl. Judy Garland does not look like Dorothy. P.S.: Please see to it that the characters look like the illustrations done by W. W. Denslow…I like those the best.’ ”

She dropped it, fluttering, back into the box.

“You see what I’m up against,” Mayer said. “Everyone has an opinion. I’ve been told that more than ninety million people have read one or more of the Oz books. Of course I don’t need to tell you that, Mrs. Baum. Oz is one of the best-known stories in the world. That’s both our blessing and our curse. So, you have opinions about how the movie should be? Well, take a ticket and stand in line.”

Maud tried to keep her composure. She had not known what to expect from Mayer, but she had not contemplated such an abrupt and thorough disregard.

“But, Mr. Mayer—”

“Is that all, Mrs. Baum? I’m a very busy man.”

Maud looked at him steadily, her mother’s daughter, even now. “No, Mr. Mayer, I’m not finished. Please hear me out. You need to understand that you have an obligation. To many people, Oz is a real place….And not just a real place—a better place. One that is distant from the cares of this world. There are children right now who are in difficult circumstances, who can escape to the Land of Oz and feel as if—”

“Of course, of course.” Mayer waved his hand dismissively. “The story is in the best hands. You have nothing to worry about, Mrs. Baum. Thank you so much for visiting today—if something comes up we’ll call….Ida, take Mrs. Baum’s phone number, would you?” He had already disengaged.

So much was riding on this encounter, Maud found herself grasping to explain. She wanted to say that she was the only person who could help them stay true to the spirit of the story, because she was the only one who knew the story’s secrets. Yet it was difficult to articulate such an imprecise thought, especially to such an abrupt and dismissive little man. So, instead of making a reasoned argument, Maud defaulted to the truth.

“I’m here to look after Dorothy.”

Mayer regarded her skeptically.

“Dorothy?”

Maud nodded. “That’s right.”

Mayer chuckled. “Judy Garland has a mother, Ethel Gumm, I’m sure you’ll find she’s quite involved in taking care of her daughter. I’d suggest you not get in her way. She’s a real fireball, that one.”

“Well, it’s not the actress I’m concerned with…” Maud said. “It’s Dorothy.”

“The cha

racter?”

“Without Dorothy, the story is nothing.”

“Mr. Mayer––” Ida Koverman interrupted, glancing at her watch. “You wanted to see Harburg and Arlen? They’re working in Sound Stage One. If you leave right now, you can catch them.”

Mayer jumped up and spun from behind the desk. “Why don’t you come with me, Mrs. Baum?” he said. “I’ll introduce you to our star. One look at our Dorothy and I’m sure your mind will be set at ease. I’m telling you, she’s divine.”

CHAPTER

2

HOLLYWOOD

October 1938

Maud could barely keep up with the small man as he bounded onto the elevator. When the twin doors slid open, she raced after him as he crossed the polished lobby floor. They emerged into a crowded alleyway where the air was, thankfully, a bit warmer than inside. After waiting for so many weeks, rehearsing her speech in her mind, she had clearly not gotten through to him. How could she explain that she wanted to be a governess to Frank’s unruly ménage of fictional creations and to fulfill her long-ago promise that she would look after Dorothy?

But she didn’t have long to dwell. Mayer was ducking in and out of the throng, striding past four costumed centurions carrying shields and swords, darting around a group of jaunty sailors, and whizzing past two ballerinas walking flat-footed in their ballet slippers and pink leotards, their pointe shoes slung over their shoulders. Soon Mayer led Maud to a large building with STAGE ONE emblazoned on the door.

“The girl is going to sing,” he said. “Big star, big star. Biggest voice you’ll ever hear. She’ll knock your socks off.”

On a stage at the far end were two men. One held a pad of paper in his hands and had a pencil stuck behind his ear; the other sat at a piano tapping out chords.

Mayer showed Maud to a seat near the back—there were rows of empty chairs, each faced by an empty music stand. He then hurried up the three steps onto the stage. He looked over the shoulder of the piano player, fidgeted with some papers on top of the instrument. He did not take a seat. His sudden appearance in the building seemed to fluster the musicians. The piano player fell silent and his head sank down on his neck, a half-submerged vessel between the oceans of his shoulders.

At first Maud thought they were alone in the room—piano player, pencil-behind-the-ear man, Louis B. Mayer, and herself—but then her eye was drawn to one corner of the stage, where a bored-looking teenage girl straddled a stool, one arm tightly folded across her chest, as if she were embarrassed by the suggestion of breasts that showed through her blouse. Could this really be Dorothy?

“Shall we take it from the top then? A one, two, three…”

The piano player warmed up with a few bars, and the girl squinted at a pad of paper she held in her hand, then put it down on her lap. The man with the pencil behind his ear looked up and caught Maud’s eye—as if he had not noticed the old woman’s presence until now—then turned back to his notepad as the piano player continued.

For a small girl, she had a big mouth, and when she opened it, the sound she made was twice as big as she was.

The notes started low and then took flight, showcasing the girl’s voice as it ascended. Maud could feel it vibrating deep within her chest, an emotion as much as a sound. She was so struck by the tone that at first she didn’t think about the words, but as she tuned into the lyrics, her face flushed. The song was about a rainbow? Where on earth had those lyrics come from? There were no rainbows in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Nobody knew about the rainbow—besides herself and Frank. She felt a momentary flicker—that there was something familiar in this girl, in this tune—but the piano hit a false note, the girl frowned, and the sensation faded.

The piano player stopped, trying out several chord progressions. Maud looked around the room, half-expecting to see Frank. Wouldn’t that be just like him? Popping his head out from behind a doorway, eyes a-twinkle. Maud loosened her collar, slipped off her sweater. Of course, Frank was not going to appear here, at Metro, in 1938. He’d been gone for almost twenty years; Maud knew that perfectly well. She was not crazy. Her mind was sharp as ever. She shifted in her seat, corrected her posture, folded her hands in her lap.

After several false starts, the piano player went on, sounding out complex, resonant chords that shifted through elegant progressions. The girl’s big voice effortlessly filled the room. When she stopped singing, the silence that followed seemed like the plain sister of a beautiful girl.

Peering at Mayer from under her dark fringe of lashes, the girl was clearly hoping for a note of affirmation.

“Oh, my little hunchback can certainly sing! Come over and give Daddy a hug,” he said.

She slowly uncoiled from her stool, unveiling a glimpse of the woman she would soon become; then, younger again, she rushed toward him, flinging her arms around the short man, so that she knocked his glasses askew. Maud watched the spectacle uncomfortably. The girl looked to be at least fifteen and was surely too old to be quite so affectionate to a grown man. Who wasn’t her father.

“And the song?” the piano player interjected.

Mayer dropped his embrace of the young actress and turned to the fellow at the piano as Judy, suddenly subdued, slunk back to her perch on the stool.

“Perfect. Excellent. Very good. Everything she sings is perfect.”

“I think the song isn’t quite right,” Maud said.

Mayer turned and stared at her, as if he had forgotten she was there.

“Perhaps just a little bit faster next time,” Mayer said.

“Not faster,” Maud said, annoyed that her voice had emerged like a mouse’s soft squeak. She cleared her throat. She had never had trouble speaking her mind—but the devil of old age was that sometimes she sounded frail when she didn’t feel it in the least.

“The song,” Maud said. “Where exactly did you say it came from?”

“Where exactly, didja say?” The piano man stood from the bench and crossed the stage, shading his eyes and peering into the darkness. “I can tell you where. I was in the car, idling at the corner of Sunset and Laurel, right in front of Schwab’s…”

Maud was instantly intrigued. “Go on.”

“That’s where it came from…popped right into my mind. I scribbled a few bars on a receipt—right there on the dashboard of my car—and as soon as the light changed, I rushed back to the studio.”

“Sunset and Laurel?” Maud said. “That’s the last trolley stop.”

“With all due respect, there’s no trolley there,” the man with the pencil behind his ear said. “The Garden of Allah Hotel is on that corner. Never seen a trolley near there.”

“I’m quite aware there is no trolley there now. I’m speaking of the year 1910. My husband and I got off the trolley there on our first visit to Hollywood.” An image of Frank rose up in front of Maud: his dust-covered white spats, crumpled gray suit, and the impressive fountain of his brown moustache as he stepped off the trolley car, onto a dirt road surrounded by orange groves, and crowed, “So this is Hollywood!”

The girl turned and stared, blinking into the dark. “Who are you?”

“Oh, we have a visitor from the Land of Oz itself—this is Mrs. Maud Baum. Her husband wrote the book,” Mayer said. “Mrs. Baum, meet Judy Garland. She is going to be a huge star!”

“My late husband wrote the book,” Maud corrected, the vivid momentary vision of Frank already fading.

“And, of course, being the widow of a man who wrote a book does not give you the slightest expertise in music,” the piano man muttered, just loud enough for Maud to hear.

But the girl seemed interested. “Why? Why do you say the song is not right?” Judy stood up from her stool and walked to the edge of the stage, peering into the shadowy hall.

“Well…” Maud breathed in slowly to calm herself, collecting her thoughts. “It’s lovely, it’s

just…something about the manner. There’s not enough wanting in it.”

“Not enough wanting?” the piano man said. “That’s preposterous.” He played a few bars, heavy on the pedal, for emphasis.

But the girl was listening. Maud could tell.

“Have you ever seen something that you wanted more than anything, but you knew you couldn’t have it? Have you ever pressed your nose right up to a plate-glass window and seen the very thing you’re longing for—so close you could reach out and touch it, and yet you know you will never have it?”

The girl’s eyes narrowed. A faint blush crept along her cheekbones, and one corner of her mouth tugged down. She twirled a lock of hair around her finger.

“Sing it like that.”

Maud studied the girl’s expression. Would this girl, this would-be Dorothy, understand? Could she understand?

“She can sing it however you want!” a woman’s voice called out from the shadows behind the stage. “Just say it, and she’ll do it. Do what the lady says, Baby. Sing it with more wanting.”

The girl’s forehead puckered, and her mouth pinched into a pout. She whirled around and hissed, loud enough for Maud to hear, “Be quiet, Mother! I’m trying to listen to the lady.”

“Just trying to help,” her mother stage-whispered back.

Maud could now make out a middle-aged woman wearing a pink blouse and white pedal pushers, standing in the shadows at the side of the stage.

“Pardon me, ma’am,” the fellow with the pencil behind his ear said to Maud. “What was it you were saying? I’m Yip Harburg, lyricist. I wanted to hear what else you had to say.” The pencil man had a shock of dark hair, and the warm flash in his brown eyes was visible behind his spectacles.

“Well, about the words…” Maud said softly. “When she sings ‘I’ll go over the rainbow,’ isn’t that a bit too certain?”

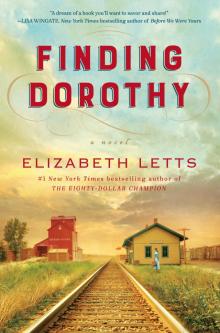

Finding Dorothy

Finding Dorothy